kottke.org posts about parenting

Play Anything is a forthcoming book by game designer and philosopher Ian Bogost. The subtitle — The Pleasure of Limits, the Uses of Boredom, and the Secret of Games — provides a clue as to what it’s about. Here’s more from the book’s description:

Play is what happens when we accept these limitations, narrow our focus, and, consequently, have fun. Which is also how to live a good life. Manipulating a soccer ball into a goal is no different than treating ordinary circumstances — like grocery shopping, lawn mowing, and making PowerPoints — as sources for meaning and joy. We can “play anything” by filling our days with attention and discipline, devotion and love for the world as it really is, beyond our desires and fears.

Reading this little blurb, I immediately thought of two things:

1. One thing you hear from pediatricians and early childhood educators is: set limits. Children thrive on boundaries. There’s a certain sort of person for whom this appeals to their authoritarian nature, which is not the intended message. Then there are those who can’t abide by the thought of limiting their children in any way. But perhaps, per Bogost, the boundaries parents set for their children can be thought of as a series of games designed to keep their lives interesting and meaningful.1

2. This recent post about turning anxiety into excitement. Shifting from finding life’s limitations annoying to thinking of them as playable moments seems similar. Problems become opportunities, etc.

3. Ok, three things. I once wrote a post about bagging groceries and mowing the lawn as games.

Two chores I find extremely satisfying are bagging groceries and (especially) mowing the lawn. Getting all those different types of products — with their various shapes, sizes, weights, levels of fragility, temperatures — quickly into the least possible number of bags…quite pleasurable. Reminds me a little of Tetris. And mowing the lawn…making all the grass the same height, surrounding the remaining uncut lawn with concentric rectangles of freshly mowed grass.

What I’m saying is, I’m looking forward to reading this book. See also Steven Johnson’s forthcoming book, Wonderland: How Play Made the Modern World.

Steven Johnson’s new book, Wonderland: How Play Made the Modern World, will be out in November. In it, he describes how novelties and games have been responsible for scientific innovation and technological change for hundreds of years.

This lushly illustrated history of popular entertainment takes a long-zoom approach, contending that the pursuit of novelty and wonder is a powerful driver of world-shaping technological change. Steven Johnson argues that, throughout history, the cutting edge of innovation lies wherever people are working the hardest to keep themselves and others amused.

Johnson’s storytelling is just as delightful as the inventions he describes, full of surprising stops along the journey from simple concepts to complex modern systems. He introduces us to the colorful innovators of leisure: the explorers, proprietors, showmen, and artists who changed the trajectory of history with their luxurious wares, exotic meals, taverns, gambling tables, and magic shows.

Here’s Johnson’s introduction on How We Get To Next.

They all revolve around the creative power of play: ideas and innovations that initially came into the world because people were trying to come up with fresh ways to trigger the feeling of delight or surprise, by making new sounds with a musical instrument, or devising clever games of chance, or projecting fanciful images on a screen. And here’s the fascinating bit: Those amusements, as trivial as they seemed at the time, ended up setting in motion momentous changes in science, technology, politics, and society.

[Ok, riff mode engaged…I have no idea if Johnson talks about learning while playing in his book, but I’ve been thinking about this quite a lot lately so…ready or not, here I come.] Being the parent of young children, you hear a lot about the power of play. I’ve never been a fan of a lot of screen time for kids, but lately I’ve been letting them play more apps on the iPad and also Mario Kart 8 on the Wii U. I’ve even come to think of their Kart playing as educational as well as entertaining. Watching them level up in the game has been fascinating to watch — Minna (my almost 7-year-old) has gone from not even being able to steer the kart to winning Grand Prix gold cups at 50cc (and she’s a better shot with a green shell than I am) and Ollie (my 9-year-old) is improving so rapidly that with his superior neuroplasticity and desire, he’ll be beating me in just a few months.1

Ok, but what is Mario Kart really teaching them? This isn’t about preparing them for their driver’s license exam. As dumb as it sounds,2 Mario Kart is a good vehicle (har!) for learning some of life’s most essential skills. They’re learning how persistant practice leads to steady improvement (something which isn’t always readily visible with schoolwork). They’re learning how to ignore what they can’t control and focus on what they can (Minna still watches green shells after shooting them but Ollie no longer does…helloooooo Stoicism). They’re learning how to lose gracefully and try again with determination. Most of all, they’re learning how to navigate an unfamiliar system. Teaching someone how to learn — knowing how to learn things is one of life’s greatest superpowers — is about exposing them to many different kinds of systems and helping them figure them out.

Update: Johnson is hosting a podcast based on the ideas in the book.

Update: Wonderland is now on sale. Johnson adapted an essay from the book on Medium called Small World After All:

The first group to build a single integrated system for global trade were the Muslim spice merchants who came to prominence in the seventh century CE. Muslim traders worked the entire length of a network that stretched from the Indonesian archipelago to Turkey and the Balkans all the way across sub-Saharan Africa. Alongside the cloves and cinnamon, they brought the Koran. In almost all the places where Muslims attempted to convert local communities through military force — Spain or India, for instance — the Islamic faith failed to take root. But the traders turned out to be much more effective emissaries for their religion. The modern world continues to be shaped by those conversions more than a millennium later. The map of the Muslim spice trade circa 900 CE corresponds almost exactly to the map of Islamic populations around the world today.

He also wrote a piece adapted from the book for the NY Times Magazine:

By the dawn of the 20th century, almost every species in the 19th-century genus of illusion was wiped off the map by a new form of “natural magic”: the cinema. The stereoscope, too, withered in the public imagination. (It lingered on as a child’s toy in the 20th century through the cheap plastic View-Master devices many of us enjoyed in grade school.) But then something strange happened: After a century of irrelevance, Brewster’s idea — putting stereoscopic goggles over your eyes to fool your mind into thinking you are gazing out on a three-dimensional world — turned out to have a second life.

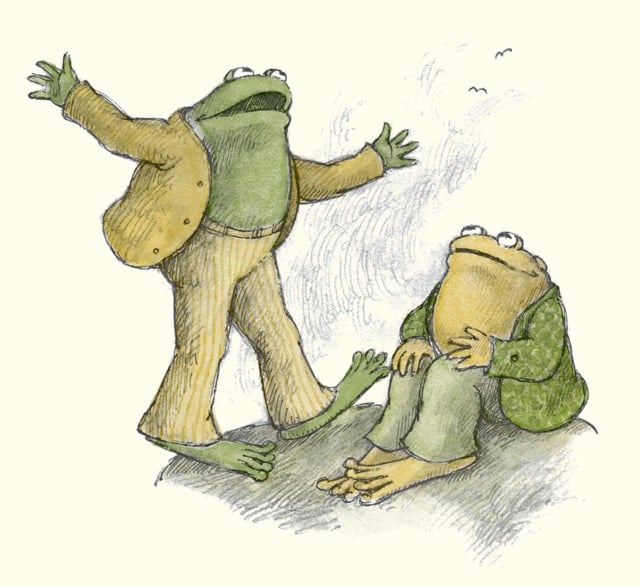

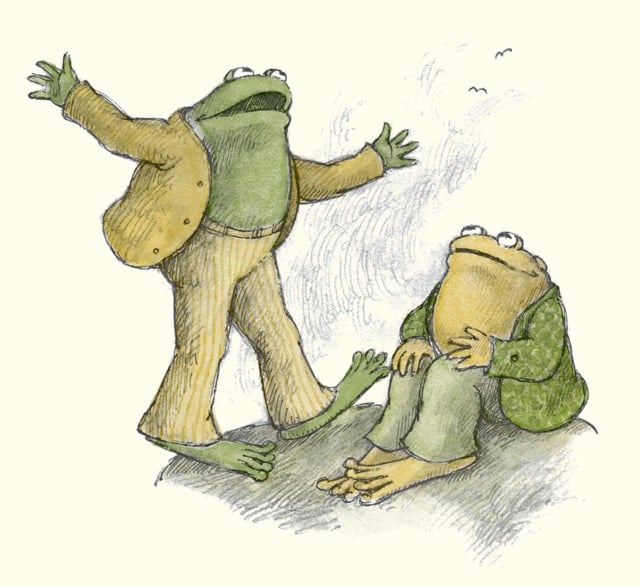

Bert Clere wrote a nice appreciation for the children’s books of Arnold Lobel, among them the Frog and Toad series and Owl at Home. Clere says Lobel’s stories offered insights for children about, yes, friendship but also about the importance of individuality.

Lobel’s Frog and Toad series, published in four volumes containing five stories each during the 1970s, remains his most popular and enduring work. Frog and Toad, two very different characters, make something of an odd couple. Their friendship demonstrates the many ups and downs of human attachment, touching on deep truths about life, philosophy, and human nature in the process. But it isn’t all about relationships with others: In the series, and in his lesser-known 1975 book Owl at Home, Lobel offers a conception of the self that still resonates decades later. Throughout his books, he reminds readers that they are individuals, and that they shouldn’t be afraid of being themselves.

Frog and Toad are favorites at our house. I’m going to read them to the kids this weekend with a new appreciation. Wanting to fit into the group is a powerful impulse for children, reinforced these days by the increased focus on group work in schools, so it’s nice to have a counterpoint to share with them.

Update: From the New Yorker’s Colin Stokes, another appreciation of Arnold Lobel. Lobel’s daughter Adrianne suspects the Frog & Toad books were “the beginning of him coming out” of the closet.

Adrianne suspects that there’s another dimension to the series’s sustained popularity. Frog and Toad are “of the same sex, and they love each other,” she told me. “It was quite ahead of its time in that respect.” In 1974, four years after the first book in the series was published, Lobel came out to his family as gay. “I think ‘Frog and Toad’ really was the beginning of him coming out,” Adrianne told me.

The article also sadly notes that Lobel died at age 54, “an early victim of the AIDS crisis”. (via @bdeskin)

Asha Dornfest runs the Parent Hacks blog and she’s collected some of her best tips into a new book, Parent Hacks: 134 Genius Shortcuts for Life with Kids.

A parent hack can be as simple as putting the ketchup under the hot dog, minimizing the mess. Or strapping baby into a forward-facing carrier when you need to trim his fingernails-it frees your hands while controlling the squirming. Or stashing a wallet in a disposable diaper at the beach-who would ever poke through what looks like a used Pamper?

Dave Pell from Nextdraft tipped me off to the book, writing:

My friend Asha Dornfest has turned her excellent parenting blog into an even more excellent parenting book with 134 ingenious ideas for simplifying life with kids. Parent Hacks is so good that I may even have a few more kids.

From Dave Eggers and Tucker Nichols comes This Bridge Will Not Be Gray (at Amazon), a children’s book about how the Golden Gate Bridge came to be painted orange.

In this book, fellow bridge-lovers Dave Eggers and Tucker Nichols tell the story of how it happened — how a bridge that some people wanted to be red and white, and some people wanted to be yellow and black, and most people wanted simply to be gray, instead became, thanks to the vision and stick-to-itiveness of a few peculiar architects, one of the most memorable man-made objects ever created.

The kids and I sat down with the book last week and they loved it. The pages on the design of the bridge prompted a discussion about Art Deco, with detours to Google Images to look at photos of the bridge,1 The Empire State Building, and the Chrysler Building. The next day, on the walk to school, we strolled past the Walker Tower, a 1929 building designed by Ralph Thomas Walker, one of the foremost architects of the 20th century. We were running a little early, so I stopped and asked the kids to take a look and think about what the building reminded them of. “Art Deco” came the reply almost immediately.

I’m really gonna miss reading to my kids — Ollie mostly reads by himself now and Minna is getting close — but I hope that we’re able to keep exploring the world through books together. NYC is a tough place to live sometimes, but being able to read about something in a book, even about a bridge in far-away San Francisco, and then go outside the next day to observe a prime example of what we were just reading is such a unique and wonderful experience.

Netflix made big news by increasing its maternity and paternity leave to a year. But in a really interesting piece, The New Yorker’s Vauhini Vara provides some historical and economic background and makes the case why not all paid family leave regulations should be left up to private employers:

Among the earners of the highest wages, twenty-two per cent have access to paid family leave, while among the lowest earners, only four per cent do. It turns out that a disparity exists even within Netflix.

Mario Koran writes about how tough it can be to be a parent (particularly a single parent) and the impossibility of describing parenthood to someone without kids. This all rings true to me, especially this bit:

I also learned that being a dad means living in constant fear. Due to dumb, random chance, or a second’s negligence, my entire world could implode at any moment. She could be electrocuted, shot, run-over, kidnapped or poisoned. She could get leukemia. It’s all there, just waiting to happen. Each week, the fear seems to grow.

During the day, I keep these emotions contained in wire mesh. I can see the feelings. I know they’re there, behind the wire. But I ignore them. I focus on work. At night, that wire mesh falls away. It’s just my wife and Lucia and me, singing Twinkle Twinkle or ABCs — or Twinkle Twinkle to the tune of ABCs. Some nights, after we tick off the lights and everything’s quiet, I feel so much I suddenly realize I’m crying.

Elsewhere, danah boyd on “the irrational cloud of fear”. Even Steve Jobs, not the best parent in the world, said that having kids is like having “your heart running around outside your body”. Not every parent feels this way, but if you are prone to anxiety, that pretty much covers it.

Screen Addiction Is Taking a Toll on Children, from Jane Brody in the NY Times:

Parents, grateful for ways to calm disruptive children and keep them from interrupting their own screen activities, seem to be unaware of the potential harm from so much time spent in the virtual world.

In reply, John Hermann writing at The Awl:

The grandparent who is persuaded that screens are not destroying human interaction, but are instead new tools for enabling fresh and flawed and modes of human interaction, is left facing a grimmer reality. Your grandchildren don’t look up from their phones because the experiences and friendships they enjoy there seem more interesting than what’s in front of them (you). Those experiences, from the outside, seem insultingly lame: text notifications, Emoji, selfies of other bratty little kids you’ve never met. But they’re urgent and real. What’s different is that they’re also right here, always, even when you thought you had an attentional claim. The moments of social captivity that gave parents power, or that gave grandparents precious access, are now compromised. The TV doesn’t turn off. The friends never go home. The grandkids can do the things they really want to be doing whenever they want, even while they’re sitting five feet away from grandma, alone, in a moving soundproof pod.

As a writer for screens, someone who spends a tremendous amount of time each day staring at screens, and an involved parent of two grade-schoolers, this is precisely where my professional and personal lives meet, so I’ve done a bit of thinking about this recently. Here’s what I’ve come up with and am attempting to actually believe:

People on smartphones are not anti-social. They’re super-social. Phones allow people to be with the people they love the most all the time, which is the way humans probably used to be, until technology allowed for greater freedom of movement around the globe. People spending time on their phones in the presence of others aren’t necessarily rude because rudeness is a social contract about appropriate behavior and, as Hermann points out, social norms can vary widely between age groups. Playing Minecraft all day isn’t necessarily a waste of time. The real world and the virtual world each have their own strengths and weaknesses, so it’s wise to spend time in both.

This advice from Amanda Hesser on how to get young kids to eat everything is 1000% solid gold:

You may wonder how we get our kids to eat kale and clams, and here is the answer: we make them (we’re warm but firm), and we don’t offer choices. Psychologists will tell you that kids respond to consistency and confidence. While I can’t say I’m great at this when it comes to bedtime, I never waver at the table. People don’t want to hear this because we live in the Age of Coddling but I strongly believe that kids need and actually crave guidance and direction, especially when they’re young. And since I also believe that we should eat the same meals as our kids — showing unity and companionship — I don’t want to eat boring food, so they’re not getting boring food.

This is exactly what we did with our kids and while it’s super difficult to be consistent and firm, especially with a picky kid, I recommend this approach wholeheartedly. My kids definitely have their preferences and would eat pizza and burgers for every meal if given the chance, but they eat a wide variety of different foods — including a lot of stuff I personally don’t care for (oysters and mussels for starters) — and are always up for trying new things. How else are they supposed to discover that they really like Sri Lankan food? (Which they do.)

Eliza Minnucci teaches a kindergarten class in Quechee, Vermont and every Monday, her students spend the entire school day outside in the forest. The results have been more than encouraging. I love this anecdote about what the forest setting can provide for students of all temperaments and abilities.

When Minnucci started this forest school experiment two years ago, she knew it would be good for the rowdy boys who clearly need to run around more than the typical school day offers.

What she didn’t expect is how good it would be for the kids who can sit still and “do” school when they’re 5 years old. She gives the example of a boy last year.

Inside the classroom, he was one of her best students. But when he got outside and kids were climbing a tree, he couldn’t get very high. “I think he was a little surprised to not be meeting his peers’ ability,” says Minnucci.

Then, partway up the tree, he fell. And got a bit scraped up. “I felt terrible,” Minnucci says. “I thought, ‘Oh this poor guy. He failed.’”

But two weeks later, when the kids were climbing the tree again, he looked over at them. “I want to try the tree,” he said.

“And he went to the tree and he got higher than he’d been before and he was beaming,” says Minnucci. “And I thought, ‘Oh, this good, this is good!’ This is a kid who may have gone so far before he met challenge that he wouldn’t have known what to do when he got there.”

Kids who are good at school need to understand there’s more to life than acing academics, says Minnucci. And students who aren’t excelling at the academic stuff need to know there’s value in the things they are good at. Doing school in the forest offers “something really important” to everyone, she says.

(via @riondotnu)

I don’t quite know what I’m doing to myself these days. Last night was an episode of The Americans in which a marriage was ending, another family was trying to keep itself intact, and a young boy struggles to move on after his entire family dies. This morning, I watched an episode of Mad Men in which a mother tries to reconcile her differences with her daughter in the face of impending separation. And then, the absolute cake topper, a story by Matthew Teague that absolutely wrecked me. It’s about his cancer-stricken wife and the friend who comes and rescues an entire family, which is perhaps the truest and most direct thing I’ve ever read about cancer and death and love and friendship.

Since we had met, when she was still a teenager, I had loved her with my whole self. Only now can I look back on the fullness of our affection; at the time I could see nothing but one wound at a time, a hole the size of a dime, into which I needed to pack a fistful of material. Love wasn’t something I felt anymore. It was just something I did. When I finished, I would lie next to her and use sterile cotton balls to soak up her tears. When she finally slept, I would slip out of bed and go into our closet, the most isolated room in the house. Inside, I would wrap a blanket around my head, stuff it into my mouth, lie down and bury my head in a pile of dirty clothes, and scream.

There are very specific parts of all those stories that I identify with. I struggle with friendship. And with family. I worry about my children, about my relationships with them. I worry about being a good parent, about being a good parenting partner with their mom. How much of me do I really want to impart to them? I want them to be better than me, but I can’t tell them or show them how to do that because I’m me. I took my best shot at being better and me is all I came up with. What if I’m just giving them the bad parts, without even realizing it? God, this is way too much for a Monday.

On a strong recommendation from Meg, I have been reading Peter Gray’s Free to Learn: Why Unleashing the Instinct to Play Will Make Our Children Happier, More Self-Reliant, and Better Students for Life. Gray is a developmental psychologist and in Free to Learn he argues that 1) children learn primarily through self-directed play (by themselves and with other children), and 2) our current teacher-driven educational system is stifling this instinct in our kids, big-time.

I have a lot to say about Free to Learn (it’s fascinating), but I wanted to share one of the most surprising and unsettling passages in the book. In a chapter on the role of play in social and emotional development, Gray discusses play that might be considered inappropriate, dangerous, or forbidden by adults: fighting, violent video games, climbing “too high”, etc. As part of the discussion, he shares some of what George Eisen uncovered while writing his book, Children and Play in the Holocaust.

In the ghettos, the first stage in concentration before prisoners were sent off to labor and extermination camps, parents tried desperately to divert their children’s attention from the horrors around them and to preserve some semblance of the innocent play the children had known before. They created makeshift playgrounds and tried to lead the children in traditional games. The adults themselves played in ways aimed at psychological escape from their grim situation, if they played at all. For example, one man traded a crust of bread for a chessboard, because by playing chess he could forget his hunger. But the children would have none of that. They played games designed to confront, not avoid, the horrors. They played games of war, of “blowing up bunkers,” of “slaughtering,” of “seizing the clothes of the dead,” and games of resistance. At Vilna, Jewish children played “Jews and Gestapomen,” in which the Jews would overpower their tormenters and beat them with their own rifles (sticks).

Even in the extermination camps, the children who were still healthy enough to move around played. In one camp they played a game called “tickling the corpse.” At Auschwitz-Birkenau they dared one another to touch the electric fence. They played “gas chamber,” a game in which they threw rocks into a pit and screamed the sounds of people dying. One game of their own devising was modeled after the camp’s daily roll call and was called klepsi-klepsi, a common term for stealing. One playmate was blindfolded; then one of the others would step forward and hit him hard on the face; and then, with blindfold removed, the one who had been hit had to guess, from facial expressions or other evidence, who had hit him. To survive at Auschwitz, one had to be an expert at bluffing — for example, about stealing bread or about knowing of someone’s escape or resistance plans. Klepsi-klepsi may have been practice for that skill.

Gray goes on to explain why this sort of play is so important:

In play, whether it is the idyllic play we most like to envision or the play described by Eisen, children bring the realities of their world into a fictional context, where it is safe to confront them, to experience them, and to practice ways of dealing with them. Some people fear that violent play creates violent adults, but in reality the opposite is true. Violence in the adult world leads children, quite properly, to play at violence. How else can they prepare themselves emotionally, intellectually, and physically for reality? It is wrong to think that somehow we can reform the world for the future by controlling children’s play and controlling what they learn. If we want to reform the world, we have to reform the world; children will follow suit. The children must, and will, prepare themselves for the real world to which they must adapt to survive.

Like I said, fascinating.

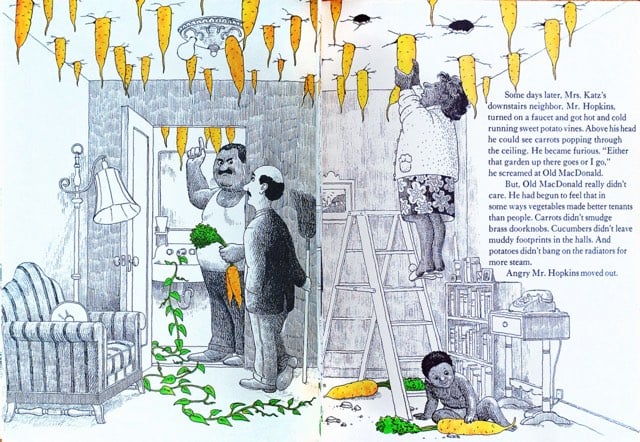

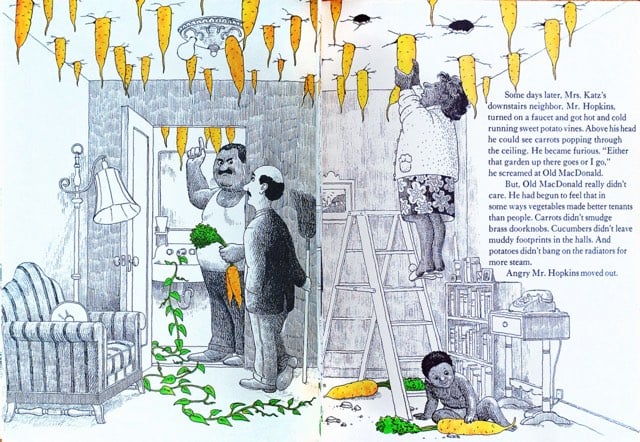

My favorite book when I was a kid was Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs by Judi and Ronald Barrett.1 So I was excited when the kids brought home a book from the library from the same authors that I hadn’t seen before: Old MacDonald Had An Apartment House. The story is about an apartment building super who starts growing food and raising livestock in vacant apartments as the increasingly alarmed tenants move out. Totally awesome 70s hippie energy crisis stuff. It didn’t click that I had actually read (and loved!) this book as a kid until we reached this page:

Love that page. Hot and cold running sweet potato vines.

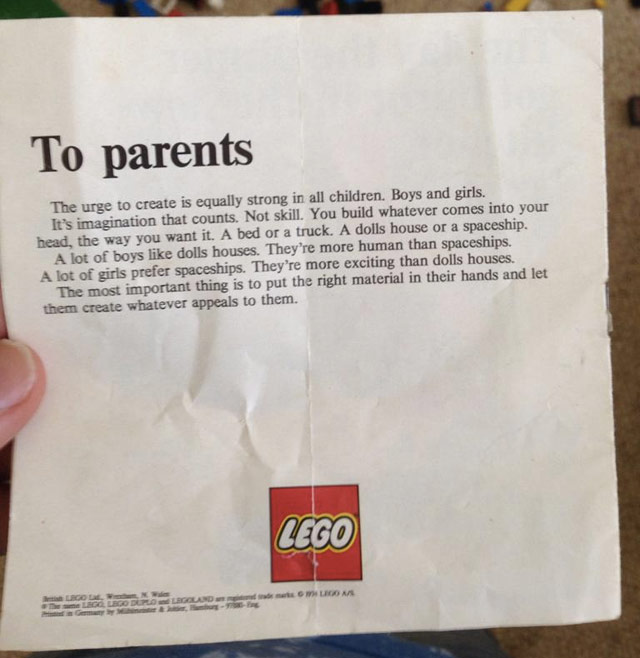

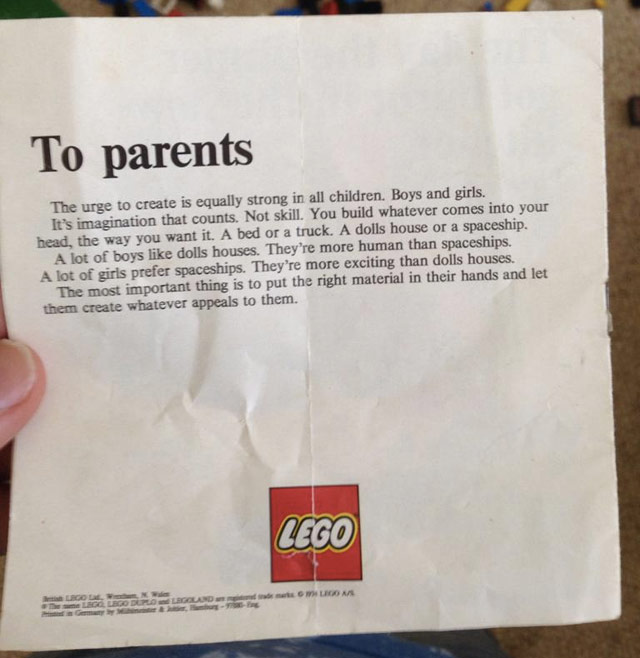

At some point in the 1970s, Lego included the following letter to parents in its sets:

The text reads:

The urge to create is equally strong in all children. Boys and girls.

It’s imagination that counts. Not skill. You build whatever comes into your head, the way you want it. A bed or a truck. A dolls house or a spaceship.

A lot of boys like dolls houses. They’re more human than spaceships. A lot of girls prefer spaceships. They’re more exciting than dolls houses.

The most important thing is to the put the right material in the their hands and let them create whatever appeals to them.

The letter seems like the sort of thing that might be fake, but Robbie Gonzalez of io9 presents the case for its authenticity.

In our home, Lego currently rules the roost…the kids (a boy and a girl) spend more time building with Lego than doing anything else. This weekend, they worked together to build a beach scene, with a house, pool, lifeguard station, car, pond (for skimboarding), and surfers. Dollhouse stuff basically. Then they raced around the house with Lego spaceships and race cars. Nailed it, 1970s Lego.

Update: QZ confirms, the letter is genuine.

For the past year, Joanna Goddard has been running a series on her blog called Motherhood Around the World. The goal of the series was to tease out how parenting in other countries is different than parenting in the US. From the introduction to the series:

We spoke to American mothers abroad — versus mothers who were born and bred in those countries — because we wanted to hear how motherhood around the world compared and contrasted with motherhood in America. It can be surprisingly hard to realize what’s unique about your own country (“don’t all kids eat snails?”), and it’s much easier to identify differences as an outsider.

The results, as Goddard states upfront, are not broadly representative of parenting in the different countries but they are fascinating nonetheless. I’ve picked out a few representative bits below. On parenting in Norway:

Both my kids attended Barnehage (Norwegian for “children’s garden”), which is basically Norwegian pre-school and daycare. Most kids here start Barnehage when they’re one year old — it’s subsidized by the government to encourage people to go back to work. You pay $300 a month and your kids can stay from 8am to 5pm. They spend a ton of time outside, mostly playing and exploring nature. At some Barnehage, they only go inside if it’s colder than 14 degrees. They even eat outdoors-with their gloves on! When I was worried about my son being cold, my father-in-law said, “It’s good for him to freeze a little bit on his fingers.” That’s very Norwegian — hard things are good for you.

The Democratic Republic of Congo:

No one thinks twice here about sharing breastmilk. Why let something so valuable go to waste? Not long after my second daughter was born, I went on a work trip to Kenya. I pumped the whole time I was there and couldn’t bear to throw away my breast milk, nor imagine the nightmare scenario of leakage in my luggage. So I saved it all up in the hotel fridge in Ziploc bags. On the day I left, I took all the little bags to the local market and said, “All right, ladies. Who’s got babies and wants breast milk?!” Not a single Kenyan woman at the market thought twice about taking a random white woman’s breast milk. My driver even heard I was handing out milk and asked if I could pump some extra to take home to his new baby.

Abu Dhabi:

There are no car seat or seatbelt laws here. You will regularly see toddlers with their heads peeking out of sunroofs or moms holding their infants in the front seat. The government and the car companies are trying to educate people about the dangers, but the most locals (Emiratis as well as people from countries like India and Egypt) believe that a mother’s arms are the safest place for her child.

India:

In a country in which space comes at such a premium, few parents would dream of allocating a separate room for each child. Co-sleeping is the norm here, regardless of class. Children will usually sleep with their parents or their ayah until they are at least six or seven. An American friend of mine put her son in his own room, and her Indian babysitter was aghast. The young children from middle class Indian families I know also go to sleep whenever their parents do — often as late as 11pm. Our son sleeps in our bed, as well. He has a shoebox of a room in our house where we keep his clothes and crib, and he always starts the night in there, falling asleep around 8pm. That way Chris and I get a few hours to ourselves. Then, around 11pm, Will somehow senses that we are about to fall asleep and calls out to come to our bed. It’s like clockwork, and he falls right back into a deep sleep the second his head hits the pillow.

Australia:

On sleep camps: Government-subsidized programs help parents teach their babies to sleep. I haven’t been to one (though I did consider it when we were in the middle of sleep hell with our daughter) but many of my friends have. The sleep camps are centers, usually attached to a hospital, that are run by nurses. Most mums I know went when their babies were around six or seven months old. You go for five days and four nights, and they put you and your baby on a strict schedule of feeding, napping and sleeping. If you’re really desperate for sleep, you also have the option of having a nurse handle your baby for the whole first night so you can sleep, but after that you spend the next few nights with your baby overnight while the nurses show you what to do. They use controlled crying and other techniques. I have friends who say it saved their lives, friends who left feeling “meh” about the whole thing, and a friend who left after a day because, in her words, “they left my baby in a cupboard to cry.”

Chile:

Giving treats to children is seen as a sign of affection, so strangers will offer candy to kids on the street. I’ll sometimes turn around and a stranger will be handing my daughter a chocolate bar! Several months ago, we were on a bus, and a woman near us was eating cookies. She saw my daughter Mia and said “Oh, let me give you some cookies.” I said, “No, thank you.” But she kept on insisting. Then, a random stranger, who was not even connected to the first woman, chimed in, “You should give your daughter the cookies!” They were very serious about it! I was frustrated at the time, but after the fact I found it funny.

And then more recently, they talked to a group of foreign mothers about how parenting in the US differs from the rest of the world. For one thing, there’s the babyproofing:

Here in the U.S., there is a huge “baby industry,” which does not exist in Romania. There’s special baby food, special baby utensils, special baby safety precautions and special baby furniture. In Romania, children eat with a regular teaspoon and drink from a regular glass. They play with toys that are not specifically made for “brain development from months 3-6.” Also, before I came here, I had never heard of babyproofing! Now I’m constantly worried about my daughter hurting herself, but my mom and friends from home just laugh at me and my obsession that bookshelves might fall.

And the more permissive and involved parenting:

I was surprised that American children as young as one year old learn to say please, thank you, sorry and excuse me. Those things are not actively taught in India. Another difference is how parents here tend to stay away from “because I said so” and actually explain things to their children. It’s admirable the way parents will go into basic reasoning to let the child know why some things are the way they are. When I last visited Bombay, I explained to my then four-year-old about that we couldn’t buy too many things because of weight restrictions in the flight, etc. My relatives were genuinely wondering why I didn’t just stop at “no.”

Like I said, the whole series is fascinating…I could easily see this being a book or documentary (along the lines of Babies).

Update: This series is back after a brief pause with installments on Korea and the Netherlands.

Update: The installment on parenting in Cuba is a good one.

On improvising in the kitchen: We often have to be resourceful and adjust our cooking plans around what we can get. At the moment, it’s been a few months since I’ve seen chicken breasts available at the market, for example. Last year on Thanksgiving, my father-in-law and I spent hours driving around trying to find potatoes, which are a black market item. People will normally walk up to you at the vegetable market and whisper, “I have potatoes.” But, that day there were none. We were like potato junkies trying to get our fix of mashed potatoes for Thanksgiving!

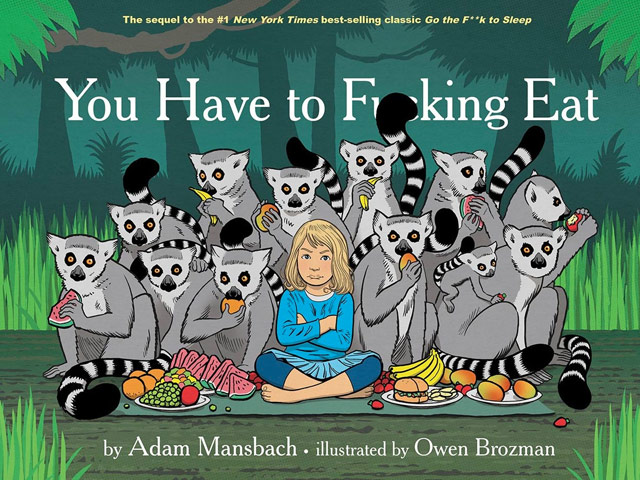

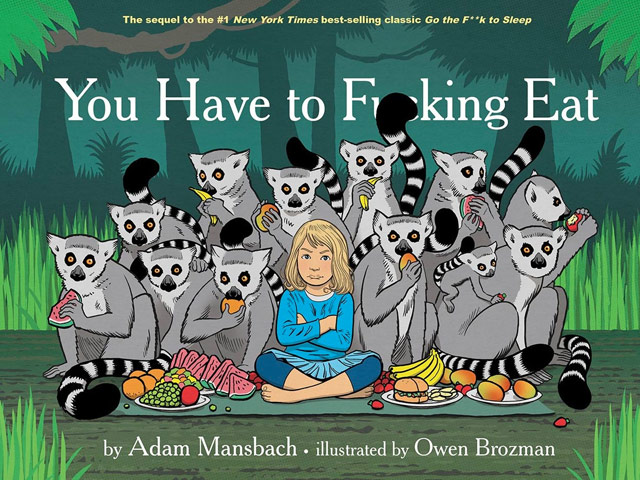

From the author of the bestselling children’s book Go the Fuck to Sleep comes a sequel of sorts: You Have to Fucking Eat.

Some recent studies suggest that reading Harry Potter may make kids nicer people.

As the familiar story goes, not long ago there was an orphan who on his 11th birthday discovered he had a gift that set him apart from his preteen peers. Over the years he endured the usual adolescent challenges — maturation, relationships, social conflicts, general teenage neuroses. He also faced the less common challenge of battling a murderous, psychopathic wizard set on establishing a eugenic police state. I’m referring to the young wizard Harry Potter, the bespeckled, morally-upright protagonist in author JK Rowling’s wildly popular fantasy book series; his nemesis is Lord Voldemort, the story’s malevolent antagonist. And, while it might sound far-fetched, new research suggests that Rowling’s world of house-elves, half-giants and three-headed dogs has the potential to make us nicer people.

I’ve been reading Harry Potter with the kids for awhile now. We’re almost finished with The Prisoner of Azkaban. One of my favorite parts of reading it with them is when they’re confused about a situation or a particular word and we get to have a conversation. While reading Chamber of Secrets, we talked about mudbloods, prejudice, and fascism. We’ve talked about good and evil and how many of the books’ characters actually possess both good and not-so-good qualities. More recently, we talked about bravery and cowardice in the context of being a friend and how even Neville, who seems frightened of everything, is a brave and true friend for trying to stop Hermione, Ron, and Harry from leaving the Gryffindor common room in search of the Sorcerer’s Stone. I don’t know if they’re better people for it, but I value the chance to have those conversations with them about something they’re really into.

Jokey t-shirts for infants are almost never funny but putting the same shirts on adults is the best idea ever.

All the designs featured are actually available for sale — here’s that I Pooped Today shirt — just click on the “See all styles” button for adult options. Ok, just one more:

(via @mulegirl)

Today at 3pm, I’m going to pick up my 6-year-old son and his friends at school and bring them back to my place for his early birthday party. We’re going to watch The Lego Movie, eat popcorn, scarf pizza, and demolish a bunch of mini cupcakes. Everyone is excited.

Today at 3pm, Eric Meyer and his family will be holding a funeral service for his 6-year-old daughter. Rebecca Meyer died on Saturday on her 6th birthday after a months-long battle against cancer. I have been following along as Eric has written beautifully and powerfully about his daughter’s illness and the family’s search for treatments. Each new piece of bad news was tough to read, and her death devastated me.

Sometimes parents tend to get caught up in the minutia of parenthood: the logistics of getting from one place to another without losing your shit, the weary deflection of the 34th “why?” question of the afternoon, and all the rest. At least, I know I do. You forget to lift your head up to appreciate what you have. Author Elizabeth Stone once wrote that having kids was deciding to “have your heart go walking around outside your body”. Steve Jobs put it similarly: your children are “your heart running around outside your body”. That’s the truest sentiment I’ve ever read about parenting; it feels exactly like that to me. Reading Eric’s writing about Rebecca, a girl so close in age to both my kids, has affected me greatly. That could be me. My kids suffering. My heart, broken and dying. Imagining one of them…I can’t even do it, the tears come hard and fast, washing away any such thoughts.

Those dark sad thoughts of mine have to be but a tiny fraction of what Eric and his family are feeling right now and in the months to come. Their heart is gone forever. Eric, I will be thinking about you and your family this afternoon even as we celebrate our happy event, while appreciating what I have more than ever. Rest in peace, Rebecca.

Note: In memory of Rebecca, the text of this post is purple, her favorite color.

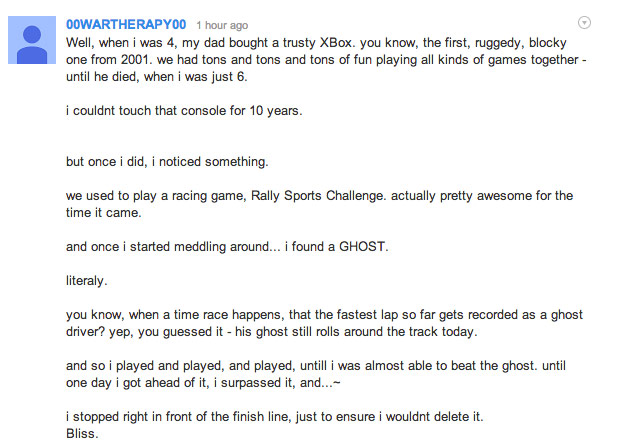

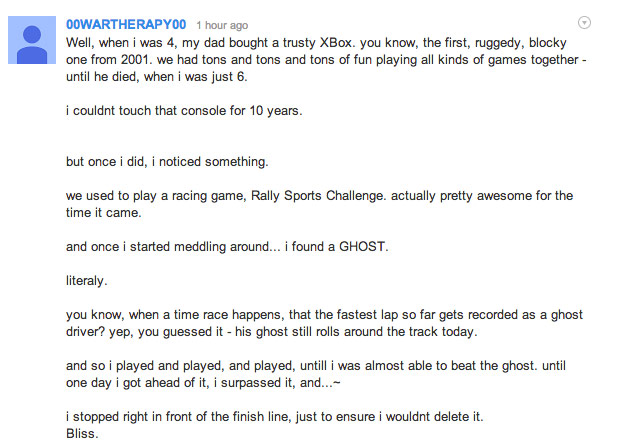

In racing video games, a ghost is a car representing your best score that races with you around the track. This story of a son discovering and racing against his deceased father’s ghost car in an Xbox racing game will hit you right in the feels.

Update: This story was originally shared in the comments of a YouTube video about gaming as a spiritual experience. (via dpstyles & @ryankjohnson)

Update: See also this story about rediscovering a loved one’s presence (and presents) in Animal Crossing. (via @shauninman)

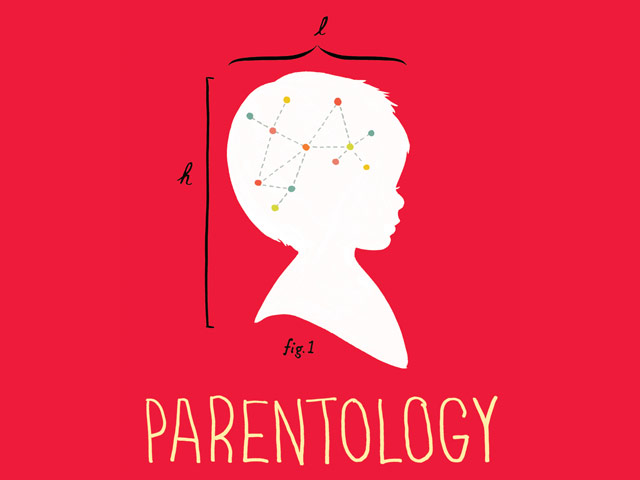

This may be the strangest parenting book I’ve ever come across: Parentology by Dalton Conley, a sociologist at NYU. In an interview with Freakonomics, Conley explains what makes his parenting approach so unconventional:

As an immigrant society with no common culture, we Americans have always made things up as we go — be it baseball, jazz or the Internet. Parenting is no different, whether we admit it or not. If we want to keep producing innovative kids who can succeed in today’s global economy, we should be constantly experimenting on them.

For example, I read the latest research on allergies and T-cell response and then intentionally exposed my kids to raw sewage (in small doses, of course) to build up their immune systems. I bribed them to do math thanks to an experiment involving Mexican villagers that demonstrated the effectiveness of monetary incentives for schooling outcomes. I perused a classic study suggesting that confidence-boosting placebos improved kids’ actual cognitive development, fed my kids vitamins before an exam, told them that they were amphetamines — and watched their scores soar.

And in this excerpt of the book from Salon, Conley explains why he and his wife named their kids E and Yo.

Unlike having fewer kids, birthing them in the Northern Hemisphere during October of a year when not many others are having kids, avoiding the mercury in fish (while still getting enough omega-3 and omega-9 fatty acids), and being rich, well-educated, and handsome to boot, there is one thing you can bequeath your kids that is entirely within your control. I’m talking about selecting their names. We may not control what race or gender we bequeath our offspring (unless, of course, we are utilizing a sperm bank in the Empire State Building for IVF), but we do have say over their names. If you play it safe with Bill or Lisa, it probably means your kids will be marginally more likely to avoid risk, too. If you’re like us and name them E or Yo, they are likely to grow up into weirdoes like their parents-or at least not work in middle management.

Early studies on names claimed that folks with strange ones were overrepresented in prisons and mental hospitals. But the more recent (and in my professional opinion, better) research actually comes to the opposite conclusion: Having a weird name makes you more likely to have impulse control since you get lots of practice biting your tongue when bigger, stronger, older kids make fun of you in the schoolyard. This study makes me happy, given the growing scientific literature around the extreme importance of impulse control and its close cousin, delayed gratification. These two, some argue, are even more important than raw IQ in predicting socioeconomic success, marital stability, and even staying out of prison.

The NightLight is a Wirecutter-esque site for baby gear: strollers, car seats, bottles, etc. headed by Gawker’s Joel Johnson and his sister, Rachel Fracassa.

Brought to you by brother-and-sister team Joel Johnson-from Consumerist, Gizmodo, and The Sweethome-and Rachel Fracassa, mother of four and doula, with contributors from Parenting, Babytalk and more, The NightLight takes the hand-wringing out of buying baby gear, with in-depth reporting and research that determines the single best product that parents should buy.

As a parent of a young child, you’re plenty busy already. The NightLight’s team of writers and researchers will help you pick the best strollers, carriers, bottles, diapers, car seats, monitors, breast pumps, and-yup-nightlights. We spend between 20 and 40 hours researching and testing on average for each guide, and in ongoing review to make sure our recommendations are always correct.

My kids are thankfully past the baby stage, but this would have been an indispensable resource 3-4 years ago.

Have you guys read the latest parenting study? The New Yorker Sarah Miller has the scoop: Parents have had enough of parenting studies.

Paul Nickman, forty-five, was taking a coffee break at his Visalia, California, law office when he began to leaf through an article about the importance of giving kids real challenges. “They mentioned this thing called grit, and I was like, ‘O.K, great. Grit.’ Then I started to think about how, last year, I’d read that parents were making kids do too much and strive too hard, and ever since then we’ve basically been letting our kids, who are ten and six, sit around and stare into space.” Nickman called his wife and started to shout, “Make the kids go outside and get them to build a giant wall out of dirt and lawn furniture and frozen peas!”

Don’t do your kid’s homework. Try not to even help them that much. It’s better for their development. And it’s better for you not to have to relive your school years. That seems like sensible advice. Until all the other parents in the school start helping their kids on their homework. That’s when you’ll be tempted. But still, really, don’t.

What they found surprised them. Most measurable forms of parental involvement seem to yield few academic dividends for kids, or even to backfire-regardless of a parent’s race, class, or level of education.

Do you review your daughter’s homework every night? Robinson and Harris’s data, published in The Broken Compass: Parental Involvement With Children’s Education, show that this won’t help her score higher on standardized tests. Once kids enter middle school, parental help with homework can actually bring test scores down, an effect Robinson says could be caused by the fact that many parents may have forgotten, or never truly understood, the material their children learn in school.

On the reading list for this weekend is Hanna Rosin’s cover story in the most recent issue of The Atlantic: The Overprotected Kid.

I used to puzzle over a particular statistic that routinely comes up in articles about time use: even though women work vastly more hours now than they did in the 1970s, mothers — and fathers — of all income levels spend much more time with their children than they used to. This seemed impossible to me until recently, when I began to think about my own life. My mother didn’t work all that much when I was younger, but she didn’t spend vast amounts of time with me, either. She didn’t arrange my playdates or drive me to swimming lessons or introduce me to cool music she liked. On weekdays after school she just expected me to show up for dinner; on weekends I barely saw her at all. I, on the other hand, might easily spend every waking Saturday hour with one if not all three of my children, taking one to a soccer game, the second to a theater program, the third to a friend’s house, or just hanging out with them at home. When my daughter was about 10, my husband suddenly realized that in her whole life, she had probably not spent more than 10 minutes unsupervised by an adult. Not 10 minutes in 10 years.

It’s hard to absorb how much childhood norms have shifted in just one generation. Actions that would have been considered paranoid in the ’70s-walking third-graders to school, forbidding your kid to play ball in the street, going down the slide with your child in your lap-are now routine. In fact, they are the markers of good, responsible parenting. One very thorough study of “children’s independent mobility,” conducted in urban, suburban, and rural neighborhoods in the U.K., shows that in 1971, 80 percent of third-graders walked to school alone. By 1990, that measure had dropped to 9 percent, and now it’s even lower. When you ask parents why they are more protective than their parents were, they might answer that the world is more dangerous than it was when they were growing up. But this isn’t true, or at least not in the way that we think. For example, parents now routinely tell their children never to talk to strangers, even though all available evidence suggests that children have about the same (very slim) chance of being abducted by a stranger as they did a generation ago. Maybe the real question is, how did these fears come to have such a hold over us? And what have our children lost — and gained — as we’ve succumbed to them?

No matter who you are, this is pretty funny. But if you have kids, it’s very nearly transcendent.

(via @ginatrapani)

Mary HK Choi spent the first dozen years of her life at odds with her mother but now she loves her so much it kills her. A lovely offbeat story of mothers and daughters.

I love my mother a not-normal amount. It’s all twisty because she tried to kill me when I was young. Just kidding. My mom is an excellent mom. She knows I am irascible, prickly and antisocial. She knows that most human interaction makes me tired and that I either scare people away with precise invectives or trot out the fakest, nicest skinjob of myself because it requires zero effort. She nails me on all of it, asking one billion follow-up questions until I get behind my eyeballs and engage. She forces me to call distant relatives, dialling the phone and pressing it into my cheek while my eyes get hot and watery. She pulls rank all the time and once judo-flipped me onto my back in a grocery store to remind me where things stood. She is my favorite and it makes me crazy. You can tell that she was popular in school, but I am a fundamentally more popular person. I care more and I’m great at rules. I’ve known it since the first grade.

The top comment on the story is well worth a read as well:

Justin went berserk.

I’d NEVER heard a kid scream so loud or for so long and still manage to run around a room tearing drawings off the wall, shoving kids all over the place, tossing chairs across the room.

It was AWESOME, in a moderately terrifying kind of way.

And the tears. Oh the tears. You’d have thought we’d taken his pet dog and made him slit its throat and then skin and cook it.

That day NEVER ended. I mean of course it did, but it never ended. You know what I mean. So, I’m hanging in the room straightening up from Justin’s rampage, when our supervisor comes in and tells me to come outside.

Which is how I met Justin’s grandparents, the two nicest, sweetest grandparents ever. No, nicer and sweeter then that. When I stuck my hand out they brushed that aside and it was semi-bear hug time. They both thanked me for what I was doing with Justin and how he didn’t talk about anything else but me.

We’re not big on TV for our kids (they watch maybe two hours a week and frequently less than that), but one show we’ve come to love watching with them is Shaun the Sheep. Produced by Aardman Animations (Wallace and Gromit), Shaun the Sheep has a number of things going for it:

- No dialogue. Not even the humans talk. Everything is communicated through grunts and gestures. Your three-year-old can follow it, as can your grandfather who only speaks Chinese.

- It’s frequently hilarious. I’ve never heard Ollie laugh so hard at anything. And not just for kids…my wife and I are usually in stitches next to them on the couch.

- Non-topical, non-contemporary. The show is almost entirely self-contained…you don’t need to know anything about pop culture to get the jokes. The humor is timeless…the show will be as good in 50 years as it is now. (There are plenty of pop culture references for the parents though…as with Bugs Bunny and Wallace and Gromit.)

- Non-violent. The humor is typically not mean-spirited and not predicated on characters hurting or attacking or making fun of other characters.

- Not gender specific. Mostly. This aspect could be a lot better (e.g. all the main characters are male), but the show is not specifically for little boys or little girls in the way that some kids shows are.

In short, it’s the perfect entertainment for 3-8 year-olds and their parents. I don’t think it’s available on Netflix Instant anymore, but you can get in on iTunes and at Amazon.

The Other F Word is a 2011 documentary about how punk rockers and other countercultural figures made the transition from anti-authoritarianism to parenthood. Features members from Devo, NOFX, Black Flag, Rancid, and also pro skater Tony Hawk. Here’s the trailer:

To be sure, watching foul-mouthed, colorfully inked musicians attempt to fit themselves into Ward Cleaver’s smoking jacket provides for some consistently hilarious situational comedy, but the film’s deeper delving into a whole generation of artists clumsily making amends for their own absentee parents could strike a resonant note with anyone (punk or not) who’s stumbled headfirst into family life.

Available to rent/buy on iTunes and on Amazon.

(via @claytoncubitt)

Older kids generally succeed better in sports, but holding kids back in school seems to have the opposite effect when it comes to academic achievement.

The researchers discovered that relatively more mature students didn’t have an academic edge; instead, when they looked at their progress at the end of kindergarten, and, later, when they reached middle school, they were worse off in multiple respects. Not only did they score significantly lower on achievement tests — both in kindergarten and middle school — they were also more likely to have been kept back a year by the time they reached middle school, and were less likely to take college-entrance exams. The less mature students, on the other hand, experienced positive effects from being in a relatively more mature environment: in striving to catch up with their peers, they ended up surpassing them.

I was the second youngest kid in my class growing up; only our valedictorian was younger. Meg was young too. And both our kids are among the youngest in the class…we didn’t redshirt them because they seemed ready for the grades they’re in. As the article states, the differences are starker now than they were…some kids in their groups are more than a year older than they are and most are several months older. NYC preschools have trouble finding a wide range of ages for each class because so many people are holding their kids back to gain a supposed competitive edge against their peers…fall kindergarten classes are full of 6-year-olds but few just-turned-fives. It’s crazy…but so much of New York is competitive like this, why wouldn’t kids’ preschool education be the same?

Newer posts

Older posts

Stay Connected